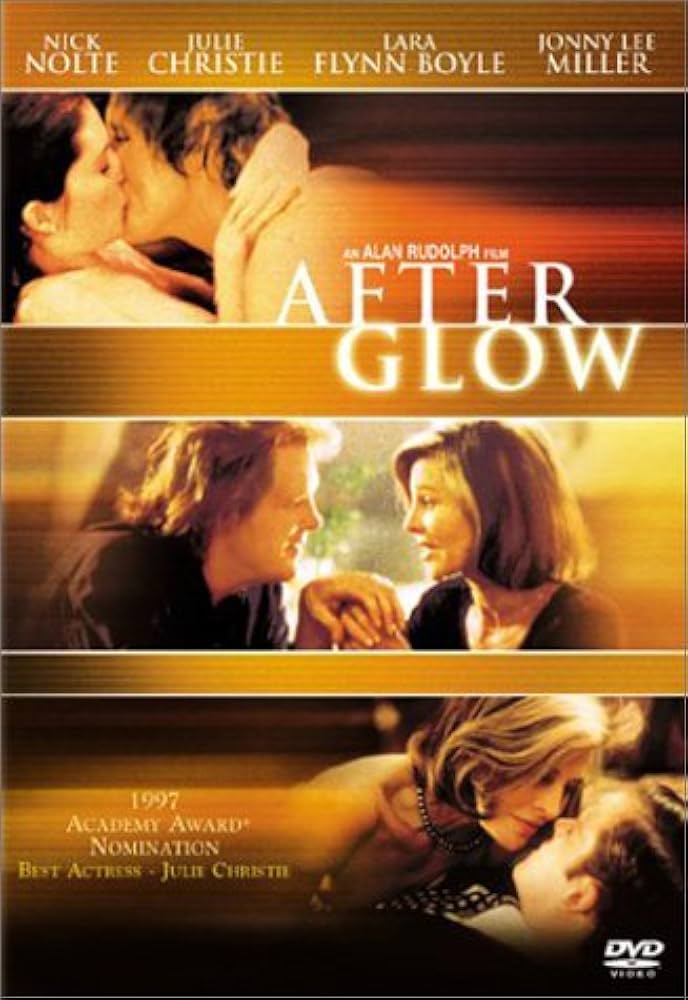

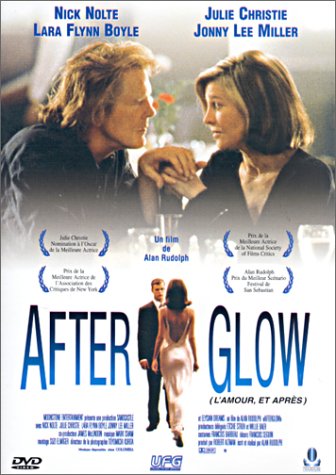

“Afterglow” (2018)

Drama

Running Time: 113 minutes

Written & Directed by: Alan Rudolph

Starring: Nick Nolte, Julie Christie, Lara Flynn Boyle and Jonny Lee Miller

Lucky Mann: “I don’t know what I like, but I know what art is.”

Afterglow is a quiet, bruised, deeply adult drama that arrived in the late 1990s almost unnoticed, yet has steadily grown in reputation as one of the most humane and perceptive films about long-term relationships, regret, and the possibility of grace. Written and directed by Alan Rudolph, the film sits firmly in the tradition of American independent cinema that privileges character over plot and emotional truth over narrative fireworks. What makes Afterglow linger is not what happens, but how it understands the damage people carry—and how gently it suggests that even late in life, something like renewal might still be possible.

At its core, Afterglow is about two marriages in crisis, though it refuses the easy symmetry of melodrama. The film opens on the deteriorating relationship between Marianne and Lucky Mann, played by Julie Christie and Albert Finney. They are wealthy Texans living in a large, beautiful house that has become emotionally airless. Lucky is a once-promising novelist who now writes ad copy, drowning his disappointment in alcohol and sarcasm. Marianne, cultured and intelligent, has grown weary of Lucky’s bitterness and inertia. Their marriage is not defined by explosive fights, but by the slow suffocation of two people who no longer know how to reach one another.

Rudolph’s script is acutely observant about this kind of marital decay. There are no villains here, only people who have failed to grow together. Finney gives one of his finest late-career performances as Lucky: abrasive, funny, and deeply sad. His anger often masks a profound sense of self-loathing, and Finney allows us to see the intelligence and sensitivity Lucky once possessed, now corroded by disappointment. Christie, meanwhile, is quietly devastating. Her Marianne is not a cliché of the neglected wife; she is strong, articulate, and painfully honest about what she needs and what she can no longer tolerate. Their scenes together are uncomfortable in the best way—conversations filled with half-finished thoughts, sharp deflections, and long silences that say more than dialogue ever could.

The film’s emotional axis shifts when Marianne begins an affair with Ben Turner, a gentle, good-hearted contractor played by Nick Nolte. Ben is married to Phyllis, portrayed by Lara Flynn Boyle, a woman suffering from deep emotional fragility and trauma. Where Lucky is caustic and verbally agile, Ben is quiet, physically imposing, and emotionally tentative. Nolte brings an extraordinary tenderness to the role, allowing Ben’s decency to feel earned rather than sentimental. He is a man worn down by years of caretaking, someone whose kindness has slowly become a form of self-erasure.

What Afterglow does particularly well is resist easy moral judgments. The affair is neither glamorized nor condemned. Instead, it is treated as a symptom—an imperfect, human response to loneliness and emotional starvation. Rudolph understands that desire often arises not from passion alone, but from the simple need to be seen and heard. The relationship between Marianne and Ben unfolds with an awkward sweetness that feels truthful, especially given the characters’ age and emotional histories. There is no illusion that this romance will magically solve their problems, only the fragile hope that it might open a door they thought was permanently closed.

Alan Rudolph’s direction is unshowy but precise. He allows scenes to breathe, often holding on actors’ faces just long enough for discomfort or realization to surface. The film’s pacing is deliberately unhurried, mirroring the emotional rhythms of middle-aged lives where change comes slowly, if at all. Cinematographer Toyomichi Kurita bathes the Texas settings in warm, muted light, reinforcing the film’s central metaphor: the “afterglow” as that soft illumination that comes not at the beginning of love, but after everything else has burned away.

The supporting performances are also key to the film’s emotional texture. Boyle’s Phyllis is a particularly risky role, as her instability could easily have tipped into caricature. Instead, she is portrayed with empathy and restraint, a woman whose pain is real and whose dependence on Ben is both understandable and destructive. Her presence complicates any simple notion of escape or happiness, reminding us that every choice carries consequences that ripple outward.

Thematically, Afterglow is preoccupied with aging—not just physically, but emotionally. It asks what happens when the dreams that sustained you in youth have either failed or been fulfilled in ways that feel hollow. Lucky’s bitterness about his stalled literary career, Ben’s quiet exhaustion, Marianne’s hunger for emotional authenticity—all speak to the terror of realizing that time is finite, and that the life you are living may be the only one you get. Yet the film is not nihilistic. Its compassion lies in acknowledging that even flawed, late-stage attempts at change still matter.

The ending of Afterglow is especially resonant because it refuses closure in the conventional sense. There are no grand reconciliations or definitive breakaways. Instead, the film offers something subtler and braver: the possibility of honesty. It suggests that facing the truth—about oneself, about one’s marriage, about one’s limitations—is both painful and necessary. The “afterglow” becomes not a promise of happiness, but a moment of clarity, a softer light in which people might finally see each other as they are.

In retrospect, Afterglow feels like a film ahead of its time. Its focus on older protagonists, its emotional maturity, and its refusal to traffic in easy sentimentality set it apart from much of the romantic drama of the era. It trusts its audience to sit with discomfort, to recognize themselves in imperfect characters, and to find meaning not in resolution but in understanding.

Ultimately, Afterglow is a film about compassion—for partners, for strangers, and perhaps most importantly, for oneself. It is a reminder that love does not always arrive with fireworks; sometimes it comes quietly, in the dim light after disappointment, offering not salvation, but the chance to go on with a little more honesty than before.re more casual, want immediate narrative gratification, or lots of bonus content, you might explore your options. poignant love stories. Brief Encounter on Blu-ray is not just a preservation of a classic, but a rediscovery of emotional cinema at its purest.