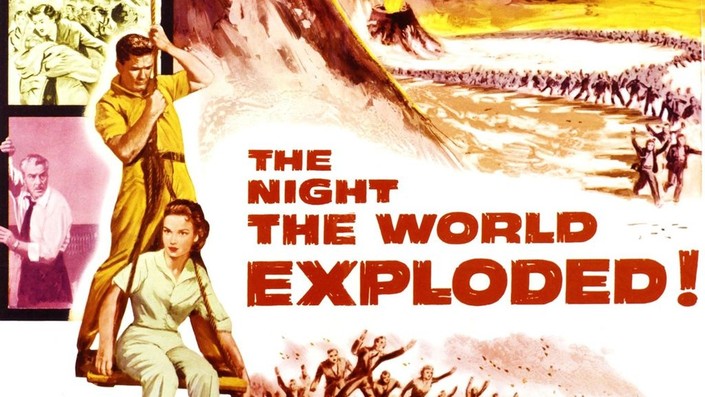

“The Night the World Exploded” (1957)

Science Fiction

Running Time: 64 minutes

Written by: Jack Natteford and Luci Ward

Directed by: Fred F. Sears

Starring: Kathryn Grant and William Leslie

Dr. David Conway: “We better do more than hope, gentlemen. We better pray!”

In the annals of 1950s B-movie sci-fi, The Night the World Exploded often finds itself overshadowed by its more flamboyant, monstrous, or technologically audacious contemporaries. Directed by Fred F. Sears, a prolific filmmaker known for churning out genre pictures, this 1957 Columbia Pictures release attempts to tap into the era’s pervasive anxieties about atomic power and the fragile balance of nature. While it largely succeeds in delivering a sense of impending doom, it does so with a methodical, almost academic pace that might test the patience of modern viewers accustomed to more immediate thrills.

The premise is quintessentially Cold War-era science fiction: a brilliant, if somewhat aloof, scientist, Dr. David Conway (played with earnest intensity by William Leslie), stumbles upon a peculiar new element, which he dubs “Element 112.” Discovered deep within the Earth, this mysterious substance exhibits an alarming property: it expands exponentially when exposed to moisture. Conway and his dedicated team, including the ever-competent Dr. Ellis Hatch (Tristram Coffin) and the more emotionally resonant Dr. Laura Nelson (Hulda Sherman, in a role that feels a little underwritten), soon realize the catastrophic implications. Subterranean pockets of Element 112 are reacting with underground water sources, causing unprecedented seismic activity – a phenomenon threatening to quite literally tear the planet apart.

What The Night the World Exploded lacks in a monster or invading aliens, it tries to compensate for with the chilling inevitability of a geological apocalypse. The film dedicates a significant portion of its runtime to the scientific investigation. We see Conway and his team meticulously analyze data, conduct experiments, and present their findings to increasingly skeptical authorities. This scientific rigor, while commendable for its attempt at realism, also contributes to the film’s deliberate pacing. For a picture with such a bombastic title, the “explosion” is a slow, agonizing process, unfolding through tremors, fissures, and the constant threat of a cataclysmic rupture.

The film’s strength lies in its ability to build tension through mounting evidence. As reports of unexplained earthquakes and land subsidence pour in from around the globe, the gravity of the situation slowly dawns on the characters and, by extension, the audience. Sears employs a mix of stock footage of natural disasters and surprisingly effective miniature work to depict the escalating chaos. While some of these effects now appear quaint, they served their purpose in conveying widespread destruction for a modest budget. The notion of the Earth itself as the antagonist, subtly expanding from within, is a genuinely unsettling concept that taps into primordial fears.

However, the film isn’t without its weaknesses. The characters, while capably played by their respective actors, often feel more like archetypes than fully fleshed-out individuals. Dr. Conway is the driven, brilliant scientist; Dr. Nelson is the intelligent female colleague who also serves as a mild romantic interest; and Dr. Hatch is the steadfast right-hand man. Their personal struggles and relationships are largely secondary to the scientific crisis, which, while understandable given the subject matter, occasionally leaves the human element feeling underdeveloped. The dialogue, too, can be a bit dry and exposition-heavy, laden with scientific jargon that might go over the heads of casual viewers.

Another noticeable element is the film’s reliance on a limited number of sets, primarily the scientific laboratory and a command center. This budgetary constraint is cleverly masked by focusing on the intellectual drama and the constant stream of news reports depicting global devastation. The black-and-white cinematography, typical of the era, adds to the somewhat stark and grim atmosphere, enhancing the sense of a world under threat.

Ultimately, The Night the World Exploded is a contemplative doomsday scenario. It’s less about spectacular action and more about the desperate race against time to understand and potentially avert an unprecedented global disaster. While it may not possess the iconic status of The War of the Worlds or the creature feature allure of Them!, it holds its own as a thoughtful exploration of scientific discovery, responsibility, and the terrifying potential for Earth’s own internal forces to unleash unimaginable destruction. For fans of classic 1950s sci-fi who appreciate a more cerebral approach to global catastrophe, and who are willing to overlook its occasional pacing issues and character thinness, The Night the World Exploded offers a chilling, if understated, vision of the end of days. It reminds us that sometimes, the most terrifying threats come not from outer space, but from within the very ground beneath our feet.