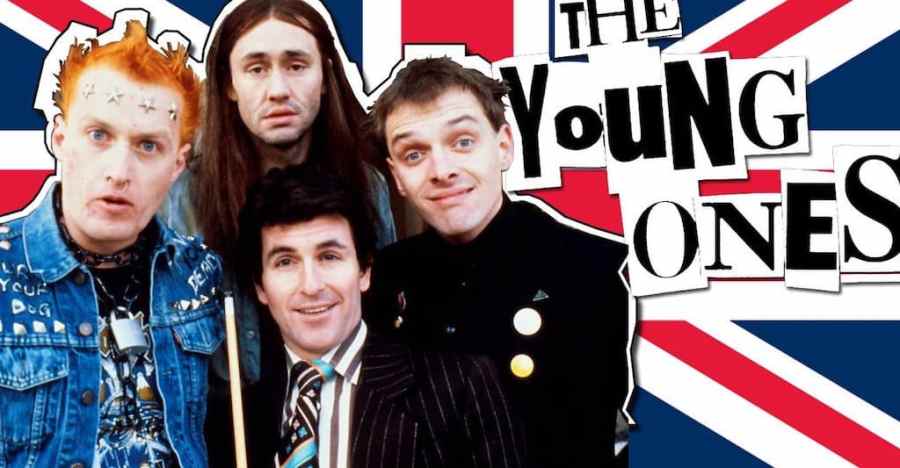

“The Young Ones” (1982-1984)

Television Series

Twelve Episodes

Created by: Ben Elton, Rik Mayall and Lise Mayer

Featuring: Adrian Edmondson, Rik Mayall, Nigel Planer, Christopher Ryan and Alexei Sayle

Rick: “I suppose you think it’s pretty weird, don’t you Mike? Well, you’d be right. ‘Cause THAT’S the kind of guy I am, right? WEIRD. Which is why I go over people’s heads. A bit like an aeroplane! You think I’m an aeroplane, don’t you, Mike? Well, I’m not.”

In the landscape of British television comedy, few series have left as disruptive, anarchic, and hilarious a mark as The Young Ones. First broadcast on BBC2 between 1982 and 1984, this bizarre, aggressive, and frequently surreal sitcom detonated onto TV screens like a Molotov cocktail of punk rock, slapstick violence, and blistering satire. Even four decades later, it remains one of the boldest comedies ever to grace the small screen—madcap, politically charged, and completely unwilling to play by the rules.

The series centers on four university students sharing a dilapidated house:

Rick (Rik Mayall) – A self-proclaimed “people’s poet,” Rick is a preening, narcissistic anarchist who worships Cliff Richard and believes he’s the moral backbone of his generation, despite being cowardly, vain, and petulant.

Vyvyan (Adrian Edmondson) – A sociopathic medical student with metal spikes in his forehead, Vyvyan is a whirlwind of destruction. He drinks motor oil, punches through walls, and maintains an intense hatred for Rick.

Neil (Nigel Planer) – A perpetually depressed hippie obsessed with lentils and gloom, Neil is the house doormat, always saddled with chores and the others’ disdain.

Mike (Christopher Ryan) – The “cool” one of the group, Mike is a small-time schemer and self-styled ladies’ man, often serving as a straight man to the others’ chaos, but just as corrupt and greedy.

These characters are not just caricatures—they’re exaggerated, weaponized versions of youth stereotypes in Thatcher-era Britain. Each represents a type of student archetype lampooned and pushed into grotesque absurdity, revealing the dysfunction beneath surface identities.

What sets The Young Ones apart is not just its cast of misfits but its form. The show frequently smashes through traditional sitcom conventions. Narrative continuity is often abandoned mid-episode in favor of surreal cutaways, puppet interludes, animated sequences, and musical numbers. Entire plotlines can hinge on the appearance of talking rats or a nuclear bomb falling on the house, only to reset completely the next week.

Some episodes barely have a story—”Boring” lives up to its title by deliberately undermining its own premise, while “Flood” ends with a siege by a vampire horde. It’s not so much a sitcom as it is a live-action cartoon with sociopolitical subtext and rock bands.

Crucially, The Young Ones wasn’t just a comedy—it was also a platform for emerging alternative culture. Each episode featured a live musical performance from then-cutting-edge acts like Madness, Motörhead, and The Damned. This wasn’t incidental: it was part of a clever strategy to classify the show as “variety” and evade the BBC’s strict comedy runtime limits.

But these performances weren’t filler—they gave the show a raw, punky energy. The Young Ones wasn’t commenting on the culture of its time; it was part of it.

Though it seems anarchic and scatterbrained on the surface, The Young Ones is a masterclass in targeted satire. Thatcher’s Britain, class divides, academic pretension, radical politics, and youth apathy are all savagely mocked. Rick’s “anarchism” is performative and shallow, a biting jab at performative activism. Neil’s peace-and-love ideology collapses under its own passive helplessness.

Even the constant violence—characters are beaten, exploded, or crushed in every episode—can be read as a critique of both the state of the world and the escapism of traditional comedy. The Young Ones doesn’t comfort the viewer—it shouts in their face and then drops a piano on them.

The Young Ones only ran for 12 episodes, but its influence is seismic. It helped launch the careers of Rik Mayall and Adrian Edmondson, who would go on to further success with Bottom and The Comic Strip Presents. The show also played a key role in the rise of the “alternative comedy” scene in the UK, paving the way for everything from Blackadderto Spaced and The Mighty Boosh.

Its subversive humor has been cited as an influence on American comedies like South Park and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, though few shows have dared to reach quite the same fever pitch of absurdity.

In many ways, The Young Ones shouldn’t work. It’s loud, messy, juvenile, and filled with gags that are more violent than clever. But therein lies its genius. It captures the manic energy of youth—its contradictions, its performative ideologies, its wild creativity—with shocking honesty and relentless hilarity.

Forty years on, The Young Ones remains a singular achievement: part sitcom, part sketch show, part punk gig, and part middle finger to the establishment. It’s not for everyone, and it never wanted to be. But for those who get it, it’s still one of the funniest, most original shows ever made.