“Shattered Glass” (2003)

Drama

Running Time: 94 minutes

Written and directed by: Billy Ray

Featuring: Hayden Christensen, Peter Sarsgaard, Chloë Sevigny, Rosario Dawson, Melanie Lynskey, Hank Azaria and Steve Zahn

Stephen Glass: “I didn’t do anything wrong, Chuck.”

Chuck Lane: “I really wish you’d stop saying that.”

In a time when journalistic integrity is under constant scrutiny, Shattered Glass emerges as both a haunting reminder and a gripping cautionary tale. Based on the true story of Stephen Glass, a young and rising star at The New Republic who was revealed to have fabricated the majority of his articles, this 2003 drama is a chilling exploration of ambition, fraud, and the fragile line between perception and truth.

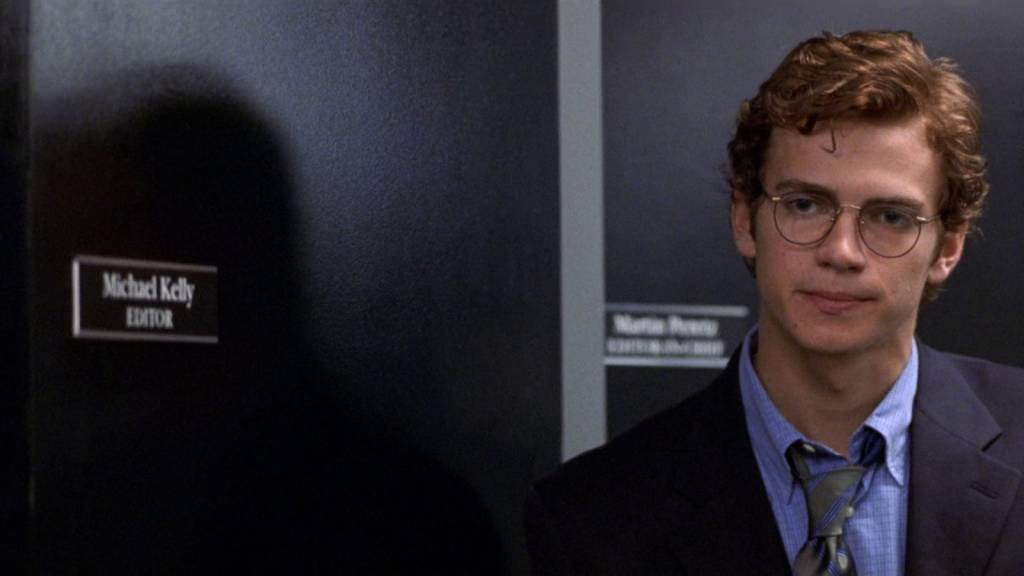

The film is set in the late 1990s, a time when The New Republic was considered the “in-flight magazine of Air Force One”—a publication with enormous cultural and political influence. Stephen Glass, portrayed with calculated vulnerability by Hayden Christensen, is a charismatic young journalist who wins over his peers with self-deprecation, humor, and apparent talent. However, as cracks begin to form in one of his high-profile stories, an editor at Forbes Digital Tool (played by Steve Zahn) begins to investigate its veracity, triggering a domino effect that ultimately exposes a vast web of deceit.

The screenplay, written by director Billy Ray, is based on the 1998 Vanity Fair article by Buzz Bissinger. It sticks closely to the real events and benefits enormously from its grounded, methodical pacing. Ray doesn’t sensationalize the scandal but rather allows the horror to build slowly through understated moments and mounting tension.

Hayden Christensen’s portrayal of Glass is arguably the best performance of his career. While known to many as Anakin Skywalker in the Star Wars prequels, Christensen demonstrates a far more nuanced range here. He plays Glass not as a clear-cut villain, but as a deeply insecure and manipulative individual who is desperate to be liked, to be seen, and most of all, to matter. His charm is disarming, and that’s precisely what makes his deception so believable—and so dangerous.

Opposite him, Peter Sarsgaard delivers a quietly commanding performance as Charles Lane, the new editor of The New Republic who must confront the possibility that his star writer is a fraud. Sarsgaard’s subtle transformation—from a cautious, slightly unsure editor trying to win over his staff, to a moral anchor determined to uphold journalistic standards—is the film’s beating heart. His restraint provides a powerful counterpoint to Christensen’s increasingly desperate Glass.

Billy Ray directs with a quiet intelligence. He avoids flashy techniques, instead choosing a clean, almost clinical aesthetic that mirrors the film’s thematic concerns. The camera often lingers on Glass’s face as he lies, catching the flickers of guilt and calculation. These moments are where the film is most powerful, inviting the viewer into the mindset of a fabricator who is not psychopathic, but profoundly weak.

What’s especially disturbing—and compelling—is how long Glass got away with it. His colleagues, editors, and even readers were enamored with his voice, his persona, and his narrative flair. The film makes clear that Glass’s success wasn’t only a personal failing; it was also an institutional one.

In hindsight, Shattered Glass feels prophetic. Released before the rise of social media, before the “fake news” crisis, and before the era of widespread digital misinformation, the film captures an earlier but no less relevant moment of moral panic in journalism. It raises enduring questions: What happens when storytelling becomes more important than facts? How do editors balance trust and skepticism? And what kind of damage can a single individual do when no one’s looking too closely?

There is a moment late in the film where Charles Lane, confronting the magnitude of Glass’s deception, says to his staff: “He handed us fiction after fiction, and we printed them all as fact. Just because we found him entertaining. It’s indefensible. Don’t you see that?” That line encapsulates the tragedy—not just of Glass’s fall, but of a collective failure to safeguard truth.

The visual style of Shattered Glass is deliberately restrained. Cinematographer Mandy Walker (later known for Hidden Figures and Mulan) gives the film a sleek, almost antiseptic look—crisp office lighting, neutral color palettes, and a general sense of order that contrasts sharply with the chaos Glass is sowing behind the scenes. The clean, quiet newsroom becomes an ironic setting: a place meant for uncovering truth that is, in reality, sheltering deceit.

There’s an eerie stillness to much of the film. Ray and Walker make frequent use of static shots and long takes, especially in scenes where Glass is spinning elaborate lies. These choices create a slow burn of tension, encouraging the viewer to scrutinize every word, every hesitation. Even Glass’s voiceovers—excerpts from his own fabricated stories—are delivered with a glossy, dreamlike quality, reinforcing the illusion he so carefully crafts for others and perhaps even for himself.

The music by Mychael Danna is similarly understated, providing a subtle emotional undercurrent without ever drawing attention to itself. It’s not there to tell you how to feel, but to gently emphasize the quiet dread of discovery, the sadness of betrayal.

What makes Shattered Glass so compelling is that it avoids pathologizing Stephen Glass. He is not presented as a sociopath or a malicious con man, but as a fundamentally insecure person whose need for approval becomes pathological. There’s something heartbreaking about his compulsions. He seems to genuinely believe that if he just tells people what they want to hear—and does it with enough charm—they’ll never stop liking him.

This emotional desperation is what makes his lies so insidious. He constructs entire stories, fake websites, voicemail lines, and even characters to prop up his fabrications. Yet when confronted, his first instinct is not self-reflection but deflection. “Did I do something wrong?” he asks, over and over. Not what he did wrong, but if. It’s the language of someone who doesn’t know where the line is anymore—or perhaps never did.

The film wisely avoids a full psychological diagnosis. Instead, it lets viewers draw their own conclusions, and in doing so, highlights a disturbing possibility: that someone can be deeply likable, even sympathetic, and still be an agent of immense damage.

Though modest in its box office take, Shattered Glass was critically acclaimed. Reviewers praised its intelligence, its tight script, and its refusal to turn a real-world scandal into melodrama. Peter Sarsgaard in particular received widespread recognition, including a Golden Globe nomination, for his portrayal of Charles Lane. In fact, some critics argued that his character arc—from soft-spoken outsider to moral compass—was the true emotional core of the film.

Hayden Christensen’s performance was more polarizing. Some reviewers were surprised by his effectiveness, given his wooden performance in Star Wars: Attack of the Clones just a year earlier. But in hindsight, Christensen’s awkwardness and anxious energy serve the character of Stephen Glass perfectly. He’s always a little too polished, a little too eager to please—qualities that, in the context of this film, make him both magnetic and terrifying.

Over time, Shattered Glass has earned a quiet but durable reputation as one of the best journalism films ever made, standing alongside All the President’s Men, Spotlight, and Zodiac. It is routinely cited in journalism schools and ethics courses, not just for its story, but for its careful dramatization of the mechanisms by which unethical behavior is enabled.

Viewed through a contemporary lens, Shattered Glass is even more chilling than it was in 2003. The lines between fact and fiction have only blurred further in the internet age, with deepfakes, conspiracy theories, and algorithm-driven news echo chambers muddying our sense of truth. In some ways, Stephen Glass feels like a proto-influencer—a person who realized early on that narrative is currency, and that audiences are often more interested in stories that feel true than in stories that are true.

The film also underscores the systemic vulnerabilities of institutions that fail to scrutinize their own stars. Glass thrived not only because he was clever, but because the culture of The New Republic was overly trusting and, at times, enamored with flair over substance. The film doesn’t wag its finger at these editors—but it does quietly indict their blindness.

In an era where media credibility is constantly under fire, Shattered Glass remains not just a historical account but a relevant, ongoing warning. It asks: what are we willing to believe, and why? And once trust is broken, can it ever be fully restored?

Shattered Glass is more than a biopic or a scandal drama. It’s an incisive character study and a morally resonant exploration of truth, integrity, and the consequences of their absence. With compelling performances—especially from Christensen and Sarsgaard—and a tightly focused narrative, the film remains one of the most intelligent and unsettling portrayals of journalistic ethics ever made.

Even more than two decades later, its message continues to echo: the truth may be boring, but it’s also essential—and infinitely more valuable than a well-told lie.

Special Features & Technical Specs:

- 1080p High-definition presentation on Blu-ray

- Audio Commentary by writer/director Billy Ray and former “New Republic” editor Chuck Lane

- Evolution and Education — interview with director Billy Ray (2025)

- Every Quote, Every Detail — interview with producer Craig Baumgarten (2025)

- Editorial Integrity — interview with editor Jeffrey Ford (2025)

- 60 Minutes: Interview with the real Stephen Glass

- Theatrical Trailer

- Aspect Ratio 2.35:1

- Audio: DTS-HD 5.1 Surround + LPCM 2.0 Stereo

- Optional English HOH Subtitles

- Limited Edition Slipcase