“The Outer Limits” (1963-1965)

Television Science Fiction

Forty Nine Episodes

Created by: Leslie Stevens

The Control Voice: “There is nothing wrong with your television set. Do not attempt to adjust the picture. We are controlling transmission. If we wish to make it louder, we will bring up the volume. If we wish to make it softer, we will tune it to a whisper. We can reduce the focus to a soft blur, or sharpen it to crystal clarity. We will control the horizontal. We will control the vertical. For the next hour, sit quietly and we will control all that you see and hear. You are about to experience the awe and mystery which reaches from the inner mind to… The Outer Limits.”

The original Outer Limits TV series, which aired from 1963 to 1965, is an iconic piece of 1960s science fiction television that has left a lasting legacy in both the genre and popular culture. Created by Leslie Stevens and developed further by writer and producer Joseph Stefano (of Psycho fame), the series offered a more cerebral and sometimes darker alternative to The Twilight Zone. Running for two seasons and a total of 49 episodes, The Outer Limits captivated audiences with its blend of speculative fiction, eerie atmosphere, and thought-provoking stories.

Each episode of The Outer Limits is a standalone story, a format that allowed the show to explore a wide range of ideas and tones, from hard science fiction to supernatural horror. The episodes were prefaced with a now-iconic narration: “There is nothing wrong with your television set. Do not attempt to adjust the picture. We are controlling transmission…” This framing device set the stage for the unusual and often unsettling stories that followed, suggesting that viewers were about to enter a dimension of mystery and control that was beyond their usual reality.

While it shared some similarities with The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits was more focused on science fiction, specifically stories of alien encounters, space exploration, and the consequences of scientific advancements. It often took a more serious, sometimes even pessimistic view of humanity’s future, leaning into the fears of the Cold War era, including nuclear annihilation, the dangers of unchecked technology, and the potential loss of humanity through alien influences.

The Outer Limits frequently addressed profound themes that resonated with the social and political climate of the 1960s. Many episodes tapped into the pervasive fears of the time, such as the threat of nuclear war, the dehumanizing effects of technology, and the consequences of scientific experimentation gone awry. For example, episodes like “The Man Who Was Never Born” delve into the moral consequences of altering time and history, while “The Architects of Fear” reflects Cold War paranoia and the lengths to which people might go to create peace through fear and manipulation.

The series also explored ethical and philosophical questions, often questioning the moral cost of scientific progress and the nature of humanity. It wasn’t afraid to challenge its audience, offering narratives that didn’t always end with a neat resolution. Many episodes concluded on a note of ambiguity or even tragedy, leaving viewers to ponder the implications of what they had just seen. This willingness to engage with complex, often dark subject matter set The Outer Limits apart from much of the other genre television of its time.

Some episodes of The Outer Limits have achieved legendary status due to their narrative inventiveness, visual creativity, and memorable performances. One of the standout episodes is “Demon with a Glass Hand,” written by the great Harlan Ellison. This episode features a man who discovers that his hand is a supercomputer containing the memories of the human race, and it blends science fiction with noir in a way that feels ahead of its time. Another Ellison-penned episode, “Soldier,” was so influential that it became the subject of a legal dispute, with Ellison accusing The Terminator (1984) of borrowing elements from his script.

Other notable episodes include “The Zanti Misfits,” which features grotesque alien creatures who are exiled to Earth, and “The Galaxy Being,” the series pilot, which features a scientist’s accidental communication with an alien entity made of electromagnetic waves. These episodes exemplify The Outer Limits’ ability to combine imaginative storytelling with unsettling, sometimes grotesque visuals.

For a 1960s television show, The Outer Limits was known for its remarkable special effects, atmospheric cinematography, and creature designs. Thanks to the involvement of cinematographer Conrad Hall, who would go on to become an Oscar-winning director of photography, the series was visually striking. The use of light and shadow, innovative camera angles, and eerie sets helped create an atmosphere of tension and dread.

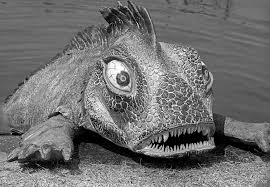

The “bear,” a term used by the creators to refer to the monster or creature featured in each episode, became a hallmark of the show. While the effects and costumes may appear dated by modern standards, they were often quite innovative for their time, and many of the creature designs remain iconic. The Zanti Misfits, with their insect-like alien appearance, and the eerie, mechanical Cylons from “The Duplicate Man” are just two examples of memorable creatures that continue to haunt viewers’ imaginations.

Though some of the visual effects have not aged well, the show’s overall aesthetic is still commendable for its ambition. The use of practical effects, makeup, and puppetry brought a sense of tangible reality to these otherworldly creatures, creating a sense of visceral unease. The show’s ability to conjure effective horror from its creatures, settings, and technology remains one of its strongest qualities.

The Outer Limits may have only lasted two seasons, but its influence can be seen in countless science fiction works that followed. Its DNA is evident in everything from Star Trek (many actors and directors from The Outer Limits later worked on Star Trek) to The X-Files, which shares The Outer Limits’ penchant for blending science fiction with horror and conspiracies. Some episodes, like “The Architects of Fear,” even served as inspiration for later works in pop culture, such as the comic Watchmen by Alan Moore.

The show was revived in the 1990s, though the original 1960s series retains a special place in the hearts of science fiction fans. Its influence on science fiction television as a genre cannot be overstated, as it laid the groundwork for a type of storytelling that combines speculative fiction with serious philosophical and ethical questions. Many of the themes it explored—such as humanity’s fear of the unknown, the ethical boundaries of scientific progress, and the potential dangers of technological advancement—are still relevant today.

One of the most defining features of The Outer Limits was the exceptional creativity behind its stories. Creator Leslie Stevens and key producer Joseph Stefano had a vision to push the boundaries of television. Stevens, a seasoned director and writer, aimed to infuse each episode with thought-provoking content that addressed both the possibilities and perils of scientific advancement. Stefano, who had already earned renown for his work on Psycho (1960), contributed a psychological depth to many of the episodes, often focusing on the internal struggles of characters grappling with existential crises or moral dilemmas.

The show regularly featured contributions from some of the most important names in speculative fiction. Harlan Ellison, in particular, became a pivotal figure in The Outer Limits, contributing two of the most memorable episodes, including “Demon with a Glass Hand” and “Soldier.” Ellison’s high-concept ideas, emotional intensity, and gift for dialogue elevated the show’s stories from mere entertainment to compelling moral and philosophical meditations. Ellison’s work on the series showed that science fiction could serve as a mirror to human nature, reflecting the conflicts and desires of the soul against the backdrop of futuristic worlds.

One of the most powerful lenses through which to view The Outer Limits is as a cultural artifact of the 1960s. Much like The Twilight Zone, the show reflected the anxieties and concerns of a world still reeling from the aftermath of World War II and living in the shadow of the Cold War. The show tapped into the fear of nuclear destruction, invasion, and the threat of “the other,” whether in the form of extraterrestrial life or subversive ideas.

Episodes such as “The Chameleon” and “The Architects of Fear” are direct reflections of Cold War-era paranoia. “The Chameleon” deals with a government operative undergoing transformation into an alien being in order to infiltrate an extraterrestrial base, only to find himself sympathizing with the creatures he was sent to observe. This story evokes the era’s fear of espionage and covert operations, as well as the existential question of identity in a world of shifting allegiances.

Similarly, “The Architects of Fear” offers a biting critique of the arms race. In the episode, a group of scientists attempts to prevent nuclear war by fabricating an alien threat, hoping to unite humanity against a common enemy. The lengths to which these men are willing to go—and the consequences of their actions—underscore the dangers of playing god with world events. The episode’s themes of manipulation, fear-mongering, and the loss of individuality in pursuit of larger political goals resonate deeply with the sociopolitical landscape of the time.

One of the hallmarks of The Outer Limits was its dedication to exploring the boundaries of scientific possibility. The series often presented futuristic technologies and alien cultures in ways that seemed plausible within the framework of the episode’s universe, and the stories consistently considered the ethical and moral dimensions of these advancements. Unlike many other science fiction shows of the time, The Outer Limits often avoided simplistic solutions, instead offering scenarios where the cost of progress could be the loss of humanity itself.

Episodes like “The Sixth Finger” delve into the dangers of human evolution and tampering with nature. In “The Sixth Finger,” a scientist devises a machine that accelerates the evolutionary process, but the subject of the experiment soon becomes too advanced for his own good, losing touch with the emotional and spiritual aspects of humanity. The episode reflects a fear of overreach in scientific exploration and the unintended consequences of meddling with natural processes—a theme that still resonates today in debates over genetic engineering and artificial intelligence.

In episodes such as “The Borderland,” where the story focuses on experiments to breach the fourth dimension, The Outer Limits tackled the unknown aspects of space-time and reality in ways that were highly speculative yet grounded in contemporary scientific theory. These high-concept stories blended real scientific curiosity with imaginative extrapolation, allowing viewers to consider both the possibilities and limitations of human knowledge. The show’s ability to weave genuine scientific inquiry into its narratives distinguished it from other TV shows of its era.

Much of the acclaim for The Outer Limits stems from its striking visual storytelling. The series benefitted from the skills of director of photography Conrad Hall, whose work helped establish an ominous, almost dreamlike atmosphere. Hall’s cinematography is renowned for its dramatic use of light and shadow, often drawing comparisons to German Expressionism and film noir. This stark visual style enhanced the psychological intensity of the series, transforming each episode into something more akin to a cinematic experience than a typical TV show.

The show’s commitment to creating an eerie, almost otherworldly atmosphere is particularly evident in its use of innovative special effects for the time. Although the show’s budget was often limited, the production team cleverly used practical effects, prosthetics, and elaborate creature designs to bring its speculative stories to life. The grotesque, insectoid Zanti Misfits, for example, are one of the most memorable creature designs in TV history. Though somewhat rudimentary by today’s standards, the blend of stop-motion effects and puppetry made the aliens in The Outer Limits both terrifying and believable for 1960s audiences.

The iconic “bear” concept that pervaded many episodes ensured that the series always had a strong visual hook. Whether it was a terrifying alien, a monstrous creature, or a visually striking representation of some technological experiment gone wrong, these bears served as physical manifestations of the episode’s themes. This visual device gave The Outer Limits a distinct identity, further cementing its place in science fiction history.

Beyond its focus on technological advances, The Outer Limits regularly touched on the most basic human ethical questions—questions about identity, purpose, and what it means to be human. In “The Inheritors,” for example, soldiers wounded in battle are mysteriously returned to life with heightened intelligence, leading them on a mission to ensure the survival of humanity. The episode touches on themes of war, sacrifice, and the potential for redemption.

Episodes like “Nightmare” and “A Feasibility Study” explore the dark consequences of captivity and human sacrifice. In “Nightmare,” soldiers from Earth are captured by an alien race and subjected to psychological torture, raising questions about the morality of war and the limits of human endurance. In “A Feasibility Study,” an entire human neighborhood is transported to an alien planet, where they are faced with the choice of either sacrificing their own freedom or dooming Earth to enslavement. These episodes pushed the boundaries of the genre by engaging with deeply philosophical questions about autonomy, sacrifice, and the greater good.

The Outer Limits remains a seminal work in the history of science fiction television. Its blend of high-concept ideas, haunting visuals, and bold storytelling helped elevate the genre during a time when science fiction was often relegated to the realm of B-movies and camp. The series dared to ask big questions, and while it didn’t always provide answers, it left audiences with a sense of wonder and unease that few other shows could match. Even more than half a century later, The Outer Limits continues to be a benchmark for thought-provoking, innovative television.