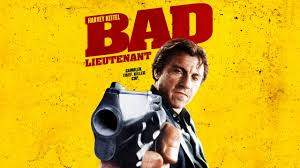

“Bad Lieutenant” (1992)

Drama

Running time: 96 minutes

Written by: Abel Ferrara and Zoë Lund

Featuring: Harvey Keitel

Zoe: “Vampires are lucky, they can feed on others. We gotta eat away at ourselves. We gotta eat our legs to get the energy to walk. We gotta come, so we can go. We gotta suck ourselves off. We gotta eat away at ourselves til there’s nothing left but appetite. We give, and give and give crazy. Cause a gift that makes sense ain’t worth it. Jesus said seventy times seven. No one will ever understand why, why you did it. They’ll just forget about you tomorrow, but you gotta do it.”

“Bad Lieutenant” is a 1992 crime drama directed by Abel Ferrara, starring Harvey Keitel in one of his most compelling and raw performances. This film is a deep dive into the tortured psyche of a morally corrupt New York City police lieutenant, whose descent into vice and degradation serves as a harrowing character study. “Bad Lieutenant” is not just about crime; it’s about the human capacity for self-destruction and the possibility of redemption, making it one of the most unsettling yet profound films of the early ’90s.

The film follows an unnamed lieutenant, played by Keitel, who is mired in addiction, corruption, and self-loathing. He spends his days engaging in illicit activities such as drug use, gambling, and abuse of power. His personal life is in shambles, characterized by estrangement from his family and a lack of meaningful connections. The plot intensifies when the lieutenant investigates the brutal rape of a nun. However, instead of simply pursuing justice, he spirals further into his vices, using the investigation as an opportunity to indulge in his darkest impulses.

Throughout the film, the lieutenant’s self-destructive behavior escalates. He loses vast sums of money on baseball bets, creating a sense of impending doom. The case of the raped nun becomes a mirror reflecting his own moral failings. Unlike him, the nun displays an unfathomable level of forgiveness towards her attackers, challenging the lieutenant’s cynical worldview. This juxtaposition of the nun’s purity and the lieutenant’s depravity is central to the narrative, driving the story toward its climax, where the lieutenant’s confrontation with the rapists becomes a pivotal moment of reckoning.

“Bad Lieutenant” is rich with themes of guilt, redemption, and the search for grace. At its core, the film examines the dichotomy between sin and forgiveness. The lieutenant’s journey is marked by a profound sense of guilt; his every action is driven by an inner torment that he cannot escape. This guilt is amplified by the Catholic iconography that pervades the film, symbolizing the lieutenant’s deep-seated religious conflict. He is a man who understands the concept of sin but finds himself powerless to break free from his vices.

The film also delves into the idea of redemption, though not in the traditional sense. The lieutenant’s redemption is not about becoming a better person but rather about reaching a state of self-awareness. His encounter with the nun’s attackers is less about justice and more about his own desperate need for catharsis. This moment is one of the most powerful in the film, as it forces the lieutenant to confront his own capacity for forgiveness. By the end of the film, his actions suggest a complex, ambiguous form of redemption—one that leaves audiences questioning the true nature of morality and atonement.

Harvey Keitel’s performance is the film’s centerpiece. His portrayal of the lieutenant is unflinchingly raw, pushing the boundaries of what audiences might expect from a leading role. Keitel’s commitment to the character is evident in every scene, from his unrestrained physicality to the emotional nakedness he brings to the role. He embodies the lieutenant’s rage, despair, and yearning for salvation with a visceral intensity that is both mesmerizing and uncomfortable to watch. Keitel’s work in “Bad Lieutenant” is often considered one of his finest performances, as he fully immerses himself in the character’s depravity, making the lieutenant both repulsive and pitiable.

Abel Ferrara’s direction is gritty and unflinching, perfectly complementing the film’s themes. Ferrara is known for his ability to portray the underbelly of urban life, and “Bad Lieutenant” is no exception. The film’s visual style reflects the lieutenant’s inner turmoil, with its grainy cinematography and unpolished look capturing the bleakness of his existence. The use of New York City as a backdrop adds to the film’s authenticity, with its dark alleys, seedy bars, and grimy streets serving as a reflection of the lieutenant’s fractured soul.

Cinematographer Ken Kelsch uses light and shadow effectively to underscore the lieutenant’s moral ambiguity. The film’s visual language often places the lieutenant in harsh, unforgiving light, highlighting his vulnerability and the severity of his situation. The city itself becomes a character, its relentless pace and unforgiving nature mirroring the lieutenant’s internal chaos. The handheld camera work creates a sense of immediacy and intimacy, drawing the audience into the lieutenant’s world in a way that is both immersive and unsettling.

“Bad Lieutenant” was controversial upon its release, primarily due to its explicit content and unapologetic portrayal of the lieutenant’s vices. The film’s graphic depictions of drug use, sexual violence, and moral degradation were shocking to many viewers and sparked debates about the limits of on-screen content. However, it is precisely this unflinching portrayal that has solidified the film’s status as a cult classic. Ferrara and Keitel did not shy away from the darker aspects of the story, instead embracing the rawness that defines the film’s impact.

The movie’s legacy extends beyond its initial reception; it has influenced numerous films and television shows that explore similar themes of moral ambiguity and the complexities of human behavior. “Bad Lieutenant” set a standard for gritty, character-driven narratives that focus on deeply flawed protagonists, paving the way for more nuanced portrayals of anti-heroes in cinema. The film also sparked a loose sequel, “Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans,” directed by Werner Herzog and starring Nicolas Cage. Though not directly connected, the sequel revisits the themes of moral corruption and personal redemption in a similarly provocative manner.

One of the most striking aspects of “Bad Lieutenant” is its relentless focus on the lieutenant’s character. Unlike traditional crime dramas that balance the protagonist’s flaws with moments of heroism, this film makes no such concessions. The lieutenant is depicted as a man almost entirely devoid of virtue, lost in a sea of addiction, despair, and nihilism. His journey is not a redemption arc in the conventional sense but rather a depiction of self-destruction, where each decision digs him deeper into his own personal hell.

His addictions are not portrayed with glamour or allure; instead, they are shown as compulsions that strip him of his humanity. Whether snorting cocaine, smoking crack, or engaging in degrading sexual encounters, the lieutenant’s actions are less about seeking pleasure and more about numbing an insatiable pain. This is perhaps best exemplified in a scene where he confronts two young women in a car, coercing them in a display of power that is both pathetic and horrifying. This moment, like many others in the film, forces viewers to witness the depths of his depravity without the usual cinematic buffers that might soften his actions.

Religion is a pervasive element in “Bad Lieutenant,” used to underscore the lieutenant’s inner conflict. Catholicism, with its emphasis on sin, guilt, and the possibility of redemption, serves as a thematic backbone. The nun’s rape case is the central narrative device that forces the lieutenant to confront his own sense of morality—or lack thereof. Her willingness to forgive her attackers contrasts sharply with his inability to forgive himself, highlighting his internal struggle.

The lieutenant’s interactions with religious icons, such as the crucifix and various statues of saints, serve as visual representations of his inner turmoil. These symbols are not just decorative; they are reminders of the spiritual and moral codes that the lieutenant continually violates. One of the film’s most intense scenes involves the lieutenant in a church, hallucinating a vision of Jesus. This moment is pivotal, as it encapsulates his desperate need for absolution, yet also his profound disconnection from any real sense of faith or forgiveness.

Ferrara uses these religious motifs not as answers but as questions, leaving the lieutenant—and the audience—to grapple with their meaning. Is the lieutenant capable of redemption, or is he too far gone? The film does not offer a clear resolution, instead leaving this question open to interpretation. The religious symbolism in “Bad Lieutenant” elevates it from a simple crime drama to a meditation on the human soul’s capacity for both evil and grace.

The soundtrack of “Bad Lieutenant” plays a subtle yet significant role in enhancing the film’s oppressive atmosphere. Ferrara, known for his use of music to underscore emotional landscapes, selects tracks that reflect the lieutenant’s chaotic inner world. The film’s score, composed by Joe Delia, combines haunting melodies with dissonant sounds that evoke a sense of dread and unease. These musical elements, paired with the diegetic sounds of New York City—the honking of car horns, the chatter of street vendors, the distant wail of sirens—create an auditory backdrop that immerses the viewer in the lieutenant’s environment.

Particularly effective are the moments of silence or minimal sound, which Ferrara uses to punctuate the lieutenant’s moments of introspection or despair. These quieter scenes allow the audience to sit with the weight of the character’s actions and the film’s themes, creating a space for reflection amidst the otherwise relentless pace of the lieutenant’s downward spiral.

“Bad Lieutenant” is often compared to Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver” (1976) in its portrayal of a man at war with his own demons, navigating a city that seems indifferent to his suffering. Both films explore themes of alienation, moral decay, and the quest for some form of justice, however misguided. However, where Travis Bickle in “Taxi Driver” seeks to cleanse the streets of its perceived corruption, the lieutenant in “Bad Lieutenant” is entrenched within that very corruption. He is not an outsider looking in; he is part of the rot that he simultaneously despises.

Another point of comparison is with Ferrara’s own earlier works, such as “King of New York” (1990), which also examines the lives of morally ambiguous characters in an urban setting. However, “Bad Lieutenant” is distinct in its unrelenting focus on a singular character’s psychological disintegration, making it a more intimate and, at times, claustrophobic viewing experience.

The film’s influence can be seen in later works that explore the complexities of anti-heroes, such as Darren Aronofsky’s “Requiem for a Dream” (2000) or Nicolas Winding Refn’s “Drive” (2011), both of which feature protagonists caught in cycles of violence and addiction. “Bad Lieutenant” helped pave the way for this darker, more nuanced approach to character study in cinema, challenging audiences to empathize with deeply flawed individuals.

Upon its release, “Bad Lieutenant” was met with polarizing reactions from critics and audiences alike. Some praised it as a masterpiece of character-driven storytelling, lauding Keitel’s fearless performance and Ferrara’s uncompromising direction. Others criticized the film for its explicit content and bleak outlook, finding it difficult to connect with a protagonist who seems irredeemable. However, over time, the film has gained recognition as a cult classic, appreciated for its bold approach and willingness to tackle difficult themes.

Critically, “Bad Lieutenant” has been analyzed through various lenses, including psychoanalytic theory, religious symbolism, and postmodernism. Scholars have explored the lieutenant’s character as a representation of the fractured modern self, torn between desire and duty, sin and salvation. The film’s refusal to provide easy answers has been interpreted as a commentary on the nature of human existence itself, which is often messy, contradictory, and unresolved.

“Bad Lieutenant” endures as a powerful, provocative exploration of the human condition. Its stark portrayal of addiction, guilt, and the elusive search for redemption challenges viewers to look beyond conventional narratives of good versus evil. Harvey Keitel’s performance remains a touchstone for actors portraying deeply troubled characters, setting a high standard for vulnerability and intensity on screen.

Abel Ferrara’s vision, though often bleak, is not without its moments of grace. The film suggests that even in the darkest corners of human experience, there exists the possibility of connection, understanding, and perhaps even forgiveness. The lieutenant’s story is not just about a man lost to his vices; it is about the struggle to find meaning in a world that offers little in the way of comfort or clarity.

In the end, “Bad Lieutenant” does not ask us to forgive the lieutenant, nor does it insist on his redemption. Instead, it presents a portrait of a man grappling with the weight of his own choices, set against the backdrop of a city that is as unforgiving as it is vibrant. It is a film that invites reflection on our own moral boundaries and the ways in which we navigate our personal journeys toward understanding and peace. In doing so, “Bad Lieutenant” remains a timeless, if unsettling, piece of cinema that continues to resonate with audiences seeking more than just entertainment, but a deeper engagement with the complexities of the human soul.

“Bad Lieutenant” is not an easy film to watch, nor is it meant to be. It challenges viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about human nature and the potential for both destruction and redemption within each of us. Harvey Keitel’s performance is nothing short of transformative, and Abel Ferrara’s direction creates a world that is as haunting as it is authentic. The film’s exploration of sin, forgiveness, and the quest for meaning in a seemingly meaningless existence is as relevant today as it was upon its release.

Ultimately, “Bad Lieutenant” is a film about a man on the edge, grappling with the weight of his own sins and searching for a way out of the darkness. It is a stark reminder of the fragility of the human spirit and the complexities of the human condition. The film doesn’t offer easy answers or a neat resolution; instead, it presents a portrait of a man whose journey is as tragic as it is compelling. For those willing to engage with its challenging content, “Bad Lieutenant” offers a powerful cinematic experience that lingers long after the credits roll.

Special Features and Technical Specs:

- 1080p High-definition presentation on Blu-ray

- Audio Commentary by director Abel Ferrara and director of photography Ken Kelsch

- It All Happens Here: Abel Ferrara & the Making of ‘Bad Lieutenant’ – documentary (2009)

- NEW All on the Line – interview with director Abel Ferrara (2024)

- NEW Forgive Me, Father: Channeling the Lord – interview with actor Paul Hipp (2024)

- NEW Entirely Uncompromised: ‘Dangerous Game’ and ‘Bad Lieutenant’ – interview with composer Joe Delia (2024)

- NEW Editor Provocateur: Crafting the Chaos of ‘Bad Lieutenant’– interview with editor Anthony Redman (2024)

- NEW Building Bad: The Making of ‘Bad Lieutenant’ – interview with producer Diana Phillips (2024)

- Theatrical Trailer

- Audio English LPCM 2.0 Stereo

- Aspect Ratio 1.78:1

- Optional English Subtitles